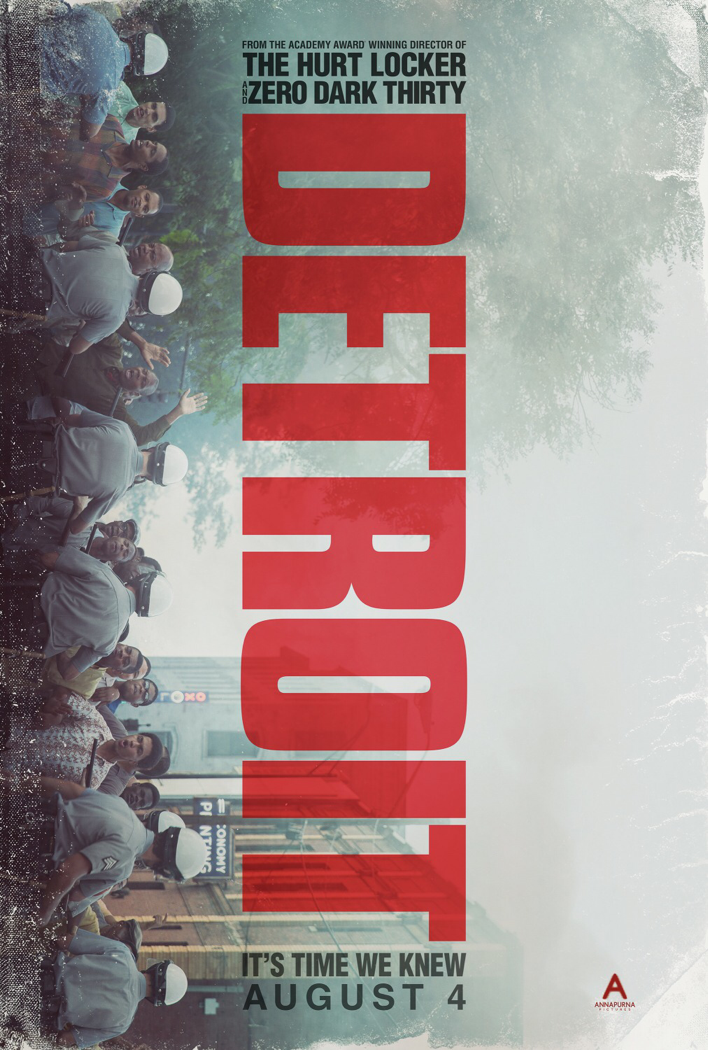

Detroit

Dir: Kathryn Bigelow

Starring: John Boyega, Anthony Mackie, Algee Smith, Jacob Latimore, Will Poulter, Jason Mitchell, Hannah Murray, Kaitlyn Dever, Jack Reynor, and Ben O’ Toole

In the summer of 1967 in Detroit, race issues between Black Americans and authority figures divided the city; turning it into a war zone of military patrolled streets filled with angry and frustrated protestors. Things were escalating for some time in Detroit before the rioting and looting began, and this was only the beginning as merely a year later Dr. Martin Luther King would be assassinated further escalating the fight for equality in America.

50 years later and the fight is still being fought; portraits of Black Americans and uniformed authority figures still flash in the media with headlines that echo sentiments of justice and injustice for a divided world. It places director Kathryn Bigelow’s film “Detroit” in an all too pertinent place in history, one which is similar to the world we live in today in both emotion and context. Ms. Bigelow’s film takes a snap shot moment from the Detroit riots and transports the viewer into an uncomfortable yet insightful place, it’s not an entertaining film but rather a bold expression of emotions that compose many of the social concerns that have and are still relevant in the world today.

“Detroit” focuses its attention on a single night, with a group of people at the Algiers motel on the west side of the city. Musician Larry (Algee Smith) and his friend Fred (Jacob Latimore) are staying at the motel, escaping the chaos of the city after a failed performance earlier in the night. The young men meet two girls, Karen (Kaitlyn Dever) and Julie (Hannah Murray), and join them at a party with some other hotel guests. Things take a terrifying turn when three local policemen, one of them still working after fatally shooting an unarmed looting suspect, and a patrol of National Guardsmen respond to reports of sniper gunfire coming from the motel.

“Detroit” focuses its attention on a single night, with a group of people at the Algiers motel on the west side of the city. Musician Larry (Algee Smith) and his friend Fred (Jacob Latimore) are staying at the motel, escaping the chaos of the city after a failed performance earlier in the night. The young men meet two girls, Karen (Kaitlyn Dever) and Julie (Hannah Murray), and join them at a party with some other hotel guests. Things take a terrifying turn when three local policemen, one of them still working after fatally shooting an unarmed looting suspect, and a patrol of National Guardsmen respond to reports of sniper gunfire coming from the motel.  Ms. Bigelow takes the events of the Algiers Motel incident and turns it into something similar to a horror film. For a large majority of the film the viewer is placed in the middle of unrelenting terror. The interrogation of a group of black men, but also two white women, is disturbing; events escalate from harsh language, to physical abuse, to mental torture, and ultimately death. Ms. Bigelow and writer Mark Boal aren’t too concerned with providing surprise developments, ingenious plot structuring, or even much of a historical lesson, instead they focus on the raw emotion of the moment, the fear that motivates action, and the individualized perception of how people remember a significant situation. While this method allows the filmmaker the opportunity to burrow into the feelings of the viewer within the specific moment, it also at times prevents the film from displaying why this moment meant so much for the city of Detroit and the civil rights movement.

Ms. Bigelow takes the events of the Algiers Motel incident and turns it into something similar to a horror film. For a large majority of the film the viewer is placed in the middle of unrelenting terror. The interrogation of a group of black men, but also two white women, is disturbing; events escalate from harsh language, to physical abuse, to mental torture, and ultimately death. Ms. Bigelow and writer Mark Boal aren’t too concerned with providing surprise developments, ingenious plot structuring, or even much of a historical lesson, instead they focus on the raw emotion of the moment, the fear that motivates action, and the individualized perception of how people remember a significant situation. While this method allows the filmmaker the opportunity to burrow into the feelings of the viewer within the specific moment, it also at times prevents the film from displaying why this moment meant so much for the city of Detroit and the civil rights movement.

“Detroit” is shot in a very specific way, with an emphasis on the feeling of chaos and uncertainty. Cinematographer Barry Ackroyd, who’s credits include “The Hurt Locker” and “United 93”, takes the camera and puts it in the middle of all the action and in the face of the characters. You can see the ignorance and blind compliance many of the people within the film are experiencing. The city burns and smolders in the background as the camera walks with characters and tightly frames them within terrible situations, in an essence trapping the viewer within the experience. It’s a technique that has been done before in cinema but the sturdy direction of a talent like Ms. Bigelow really makes this technical choice shine.

As the film ventures further into the tragic events of the evening, the film begins to lose its way. Instead of developing the situation and characters in delicate and subtle ways, like they do with the relationship of two friends or with the motives of a security guard (John Boyega) trying to promote peaceful relationships, the film resorts to a disordered commentary promoted by violence and brutality.

“Detroit” is many times an observant look at a complicated, appalling situation. The opening of the film sets the precedent that issues in Detroit, but also in America, were at a boiling point; it was a progression of events highlighted by discrimination, segregation, and the abuse of authority and it slowly happened over decades of time. While the narrative never encapsulates the point of how rebellion led to change or how this change played a role in shaping American sentiments at the time, it does painfully display how familiar the past can look in the present.

Monte’s Rating

3.75 out of 5.00

No comments:

Post a Comment